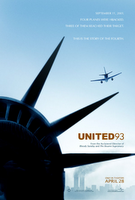

Martin Amis finds "United 93" unremitting, stark and utterly moving

At 8.21 the first plane, American 11, turned off its transponder (the automatic tracking device); then it changed course and began its descent. The air-traffic controllers were still trying to locate American 11 when word came through that “a light plane” had hit the World Trade Centre. On CNN the controllers see the site of the crash. The wound in the building’s side is in the shape of a plane: not a Cessna or a twin-prop but what they call a “heavy” — a Boeing 757.

At 8.21 the first plane, American 11, turned off its transponder (the automatic tracking device); then it changed course and began its descent. The air-traffic controllers were still trying to locate American 11 when word came through that “a light plane” had hit the World Trade Centre. On CNN the controllers see the site of the crash. The wound in the building’s side is in the shape of a plane: not a Cessna or a twin-prop but what they call a “heavy” — a Boeing 757.In the real-time docudrama United 93, we see the second plane strike its target, not on CNN, but with the naked eye. What appears to be the original footage, startlingly, has been placed within a vast vista of morning blue. Our POV is the control post at Newark International.

By now the North Tower, to the right, is like a demonic smokestack, giving off a leaning column of furry black fumes. As United 175 impends, the controllers gasp at its velocity. Mohammed Atta’s incision, in the North Tower, will now look surgically discreet — compared to the kinetic ecstasy sought by Marwan al-Shehhi. United 175 was travelling at nearly 600mph, a speed that the 767 was not designed to reach, let alone sustain. This happened eleven seconds and three minutes after nine o’clock — the core moment of September 11. Now they knew. And so did the passengers on United 93.

That plane, too, was travelling at 580mph when it crashed, nose first and upside down, forming a crater 175ft deep in an empty field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Of the 3,000 who died on that day, only those on board the fourth plane had no doubts about the fate intended for them. The director of United 93, Paul Greengrass, is right: they were “the first people to inhabit the post-9/11 world”. We may strongly identify with one passenger, an earnest Scandinavian, who cannot accept the new reality: he argues for full co-operation with the hijackers, hoping, one assumes, for a leisurely siege on some North African tarmac. The others know, from cellphones and airphones, that it isn’t going to be like that. They rise up, and the plane comes down.

At this point, 106 minutes in and with only seconds to go, you will find yourself, I am confident, in a state of near-perfect distress — a distress that knows no blindspots. The New York Times called United 93 “the feel-bad movie of the year”. But this hardly covers it. The distress is something you can taste, like a cud, returned from the stomach for further mastication: the ancient flavour of death and defeat. Your mind will cast about for a molecule, an atom of consolation. And what you will reach for is what they reached for. Like the victims on the other three planes, but unlike them, because they knew, the passengers called their families and said that they loved them. It is an extraordinary validation, or fulfilment, of Larkin’s lines at the end of An Arundel Tomb:

...To prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

A Hollywoodised version of the story would begin with Bruce Willis, in the part of Todd Beamer (“Let's roll”), waking in Manhattan, and languidly reminding his wife that he is off to San Francisco on an early flight from Newark. United 93 begins with the desolate, self-hypnotising drone of early-morning prayer. In their budget hotel room the four hijackers, wearing clean white vests, are aspiring to the murderous serenity urged on them by their handlers in Afghanistan.

Soon they are among the passengers and are being processed to the gate. We are in the familiar, and suddenly painful, everyday: the spotty young woman with her laptop; the shared travel anxiety of an elderly couple; the grunt of relief from a panting young man, pleased, as you would be, to get there just in time. And it is here, in the departure bay, that Greengrass makes his one major divergence from the known: Ziad Jarrah, the pilot and leader (and literally a different breed from the “ muscle” Saudis), says six words into his mobile phone — “I love you. I love you.”

Greengrass may have other sources. According to a footnote in the 9/11 Commission Report, Jarrah did make a final call to his fiancée, Aysel Senguen; but he called her from the hotel, and she described their conversation as brief and not unusual. Thus the moment in the departure bay, though broadly justifiable, is hugely anomalous, and for this reason: it is artistic. And elsewhere, while Greengrass cannot banish his talents of eye and ear, he refuses, quite rightly, to be artistic.

Those six words hang in the air, and are balanced and answered by the tearful protestations of the doomed passengers. In this reading, Jarrah, too, knew what would survive of him.

What is not in doubt is that Jarrah loved Aysel Senguen. He is, by many magnitudes, the least repulsive of the 19 killers of September 11, 2001. An affluent Lebanese, he left the beaches and discos of Beirut at the age of 21, in 1996, and went to Germany to study dentistry (he later switched to aeronautics). There he met and fell in love with Aysel Senguen, the student daughter of a Turkish immigrant. He was human in other ways. Defying cell policy, he stayed close to his family, and made several returns to the bedside of his ailing father in Lebanon. Most centrally, he had doubts, and needed to be cajoled and rallied right to the end. And all this is there in the extraordinary performance of Khalid Abdalla. There are no weak points, and no obtrusively strong points, in the United 93 ensemble. But among the little-knowns and the unknowns and the people playing themselves, Abdalla, perhaps destabilisingly for the movie, is something like its star. His history is all held in, yet it is all there in his suffering eyes.

At Newark International there was a routine — indeed wholly predictable — delay on the ground, caused by weight of traffic. Those 42 minutes changed everything. If United had left on time, there would have been no passenger revolt. Instead, there would have been horror at the White House or horror at the Capitol.

Osama bin Laden wanted the White House. Mohamed Atta, the operational leader, vaguely argued that the approach would be too difficult, and wanted the Capitol. Interestingly, the President was not in the White House (he was puzzling his way through My Pet Goat in Sarasota, Florida), but the President’s wife might well have been in the Capitol (pushing No Child Left Behind). In any case, both buildings were evacuated by 9.30 — two minutes after the hijack of United 93.

Greengrass peels off, at punctual intervals, to follow the traffic controllers (whose efforts were highly impressive) and to follow the military (whose efforts were pitiable); but by now the other three planes have crashed, and the focus is all on United 93. Sickening suspense about the revolt of the terrorists is replaced, thereafter, by sickening suspense about the revolt of the passengers. In the aftermath of that day, a CIA official noted that, even though the state spent $40 billion a year on internal security, all that stood between America and September 11 was “a bunch of rugby players”. But America didn’t even have that. There is no bunch, no pack, of rugby players. There is one huge athlete who spearheads the charge (with a marvellously giddy, drunken expression on his face); but he leads a motley band — they are just passengers, after all. The countercoup is rendered in strict accordance with Greengrass’s method. There is no final pow-wow, there are no husky valedictions. It simply erupts, with desperate suddenness, and they are coming down the aisle with their weapons — kitchen knives, wine bottles, boiling water.

And they didn’t really have a chance. This was one of the existential nightmares of United 93. They were up in the sky at maximum throttle in a huge machine. But no one on board knew how to land it. Not Jarrah, who was trained only for level flight. By now the passengers are using the drinks cart as a battering-ram, and Jarrah, lover of Aysel Senguen, is doing what he can to make the plane yaw, then pitch, then dive. These are the last words on the black box, translated from the Arabic, each and every one utterly futile, and utterly meaningless. “Allah is the greatest! Allah is the greatest! Is that it? I mean, shall we put it down?” “Yes, put it in it, and pull it down.” We can say, at least, that the passengers saved America from a fourth scar on its psyche. And there is that glimmer of double meaning in the film’s title. And that is all.

Greengrass doesn’t spare us — but he spares us something. When was the last time you boarded an aeroplane that had no children in it? United 93 has no children in it. It is hard to defend your imagination from such a reality. “What's happening? You see, my child, the men with the blood-stained knives think that if they kill themselves, and all of us, they will go at once to a paradise of women and wine.” No, I suppose you would just tell him or her that you loved them, and he or she would tell you that they loved you too. Love is an abstract noun, something nebulous. And yet love turns out to be the only part of us that is solid, as the world turns upside down and the screen goes black. We can’t tell if it will survive us. But we can be sure that it’s the last thing to go.

Times Online

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home